Automotiva Obscura is your (incredibly nerdy) dose of rare, odd, obscure, or otherwise unknown automobilia.

In 1957, Ford introduced what may be the single greatest rear axle ever conceived: The Ford 9 inch. This thing had it all–large diameter ring gear, fully removable pinion and center section, large carrier bearings, and a strong case. Even so, for the 1966 model year, Ford-Lincoln-Mercury engineers tried to up the ante.

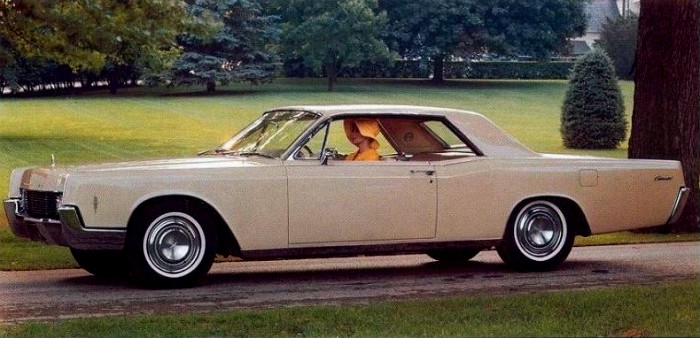

Enter the Ford 9 3/8″ rear axle. Bigger? In ring gear only. Better? Sort of. Let me explain. By 1966, Ford’s lineup (including Mercury and Lincoln) had been quickly growing in size, weight, engine displacement, and most importantly, power. The 428ci version of the venerable FE engine series was being put into heavier, full size cars. The 430ci MEL (Mercury, Edsel, Lincoln) V-8 had just been replaced by its massive 462ci successor in Lincolns and full-size Mercuries. Would the regular 9 inch be adequate for these applications? Most likely. But by 1966, Ford was at the top of its game, especially in the full-size and personal luxury segments–Ford Thunderbirds, Lincoln Continentals, Mercury Montereys, etc. Why risk differential failure, especially in the most expensive cars in the lineup that have the most brand image and prestige to uphold?

The jump from the regular Ford 9 inch to the 9 3/8″ is actually quite a straightforward one. The 9 3/8″ housing is just a slightly modified 9″ housing, with a bit more clearance for the larger ring gear. All 9 3/8″ rear differentials use the same 31 spline axles and larger bearings as the large bearing version of the 9″. In fact, a 9 3/8″ center section will fit into a 31-spline 9″ housing with only minor clearancing for the larger ring gear. Conversely, a large bearing 31-spline 9″ 3rd member will bolt right into a 9 3/8″ housing (The small bearing 28-spline 9″ center section will not). In this way, Ford was able to add strength in the center section for heavier, more powerful cars, while reducing costs by retaining the outer housing and axle assemblies from the existing 9″ rear end.

From 1966-1977 in select full size Fords, Lincolns, and Mercuries, and from 1968-1972 in 1/2 ton pickup trucks (with limited availability), the 9 3/8″ rear end reliably put big-block power to the ground in some of the largest vehicles America had to offer. Most, if not all, Lincolns and Mercuries with the 462ci MEL V-8 utilized the oddball 9 3/8″ rear end, as did many Thunderbirds optioned with the 428 (and later 429) V-8s. Some 428-equipped full sized Fords, Mercuries, and Lincolns (Galaxies, Montereys, etc.) also received the 9 3/8″, although it is less clear if it was standard with the 428, optional, or part of a heavy-duty or towing package. The same is true of later 429ci and 460ci full-size cars and wagons until 1977. Likewise, in 1/2-ton pickups one would be much more likely to find a 9 3/8″ in a 390-equipped truck with a towing package or other “heavy duty” appointments. Unfortunately, being a relatively rare and unknown rear axle, available documentation for the 9 3/8″ is rather lacking. There is no mention of an available larger rear axle in any Ford brochure that I can find from 1966-1977. The 1968-72 Ford Pickups brochures lists two axle options for 1/2 ton offerings, but that could just as easily be the small and large bearing standard 9-inch.

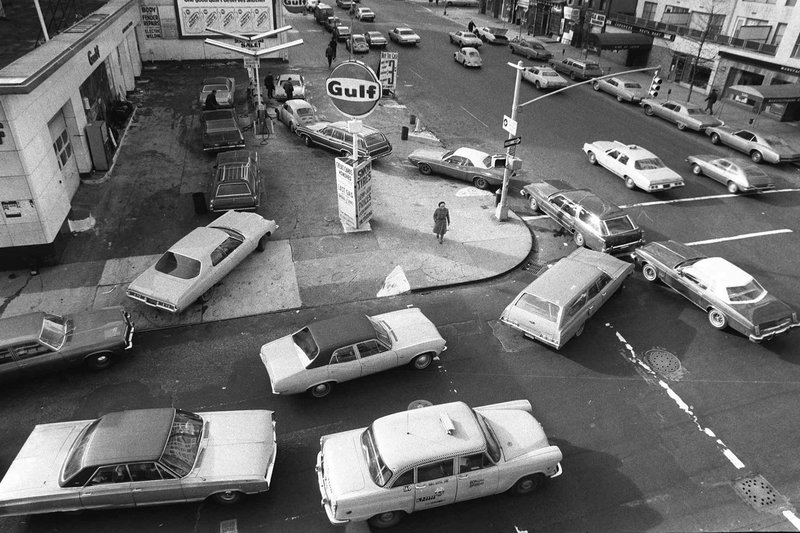

The 9 3/8″ rear end had an interesting and largely unknown 11-year run from 1966-1977, especially compared to the standard 9-inch, which Ford produced from 1957 through the 1986 model year. By 1977, the 9 3/8″ rear axle had outlived its usefulness. The large cubic-inch MEL- and FE- series big blocks had been discontinued in passenger cars, leaving only the 385-series big blocks, (429ci and 460ci V-8s) with lower outputs than their predecessors. By 1978, the big-block 460 had been phased out of passenger cars, and the 3/4 and 1 ton trucks it remained in used heavier duty truck differentials. For the remaining high-performance/high strength applications, Ford had the much stronger nodular iron case 9″. Furthermore, by 1977, the United States was still recovering from a recession and fallout from the 1973 oil embargo. Thirsty large displacement V-8s and large, expensive cars were quickly losing popularity. There simply was no longer any justification to produce a unique center section when the proven and more widely produced 9-inch was perfectly adequate.

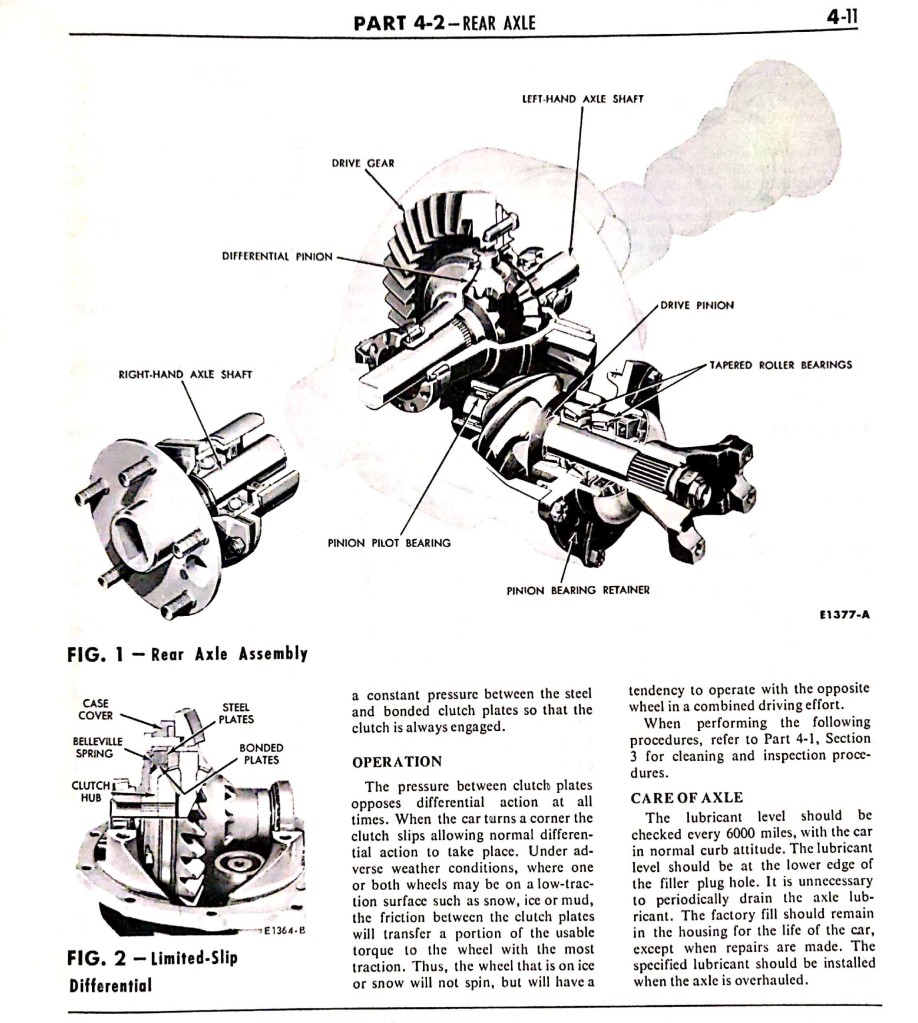

If you’re headed to the junkyard to find a heavy duty axle for your project, the 9 3/8″ rear end can be identified by two widely spaced vertical ribs cast into the 3rd member. Be careful not to confuse this with the later 9-inch 3rd member with more closely spaced vertical ribs. Many 9 3/8″ center sections have provisions for different oddball flanges instead of the standard 9″ style yokes, so it may be worth it to grab the driveshaft from the donor as well. Factory gear ratios are limited, generally 2.50:1, 2.80:1, or 3.00:1 as was standard in most Fords of the era, with the oddball 3.25:1 thrown in there. 3.50:1 gears were available in 9 3/8″ equipped trucks. There are reports that a 4.10:1 ratio was offered for one year in trucks, but this is difficult to verify. The 9 3/8″ was never available in a true high-performance application or trucks larger than 1/2 ton where low (numerically high) gear ratios are common. Limited slips were available, but rebuild kits for the oddball carriers are no longer available. The only way to determine whether or not a given 9 3/8″ is equipped with a limited slip is to check the ratio tag on the differential for an “L”. There is no other outside indicator or rule to find the limited slip rear ends. Trucks equipped with the 3:50:1 ring and pinion are alleged to more commonly have limited slip carriers.

However, a 9 3/8″ rear end makes a great housing donor for a 31-spline 9-inch center section. Or just drop it to a cruiser or street rod as-is and educate everyone who asks “you mean a 9-inch, right?” at your next car show.

Special acknowledgement to my father for digging out his ’66 T-Bird service manual to send scans of the axle section.

Wow, thanks for the in-depth article! I had no idea the third member from a 9″ would fit in a 9 3/8″!

LikeLike