Feast your eyes on what is, in my opinion, the most beautiful mass-market motorcycle ever sold in America: the 1989-90 Honda GB500 Tourist Trophy. The GB500, introduced to the Japanese market in 1985, didn’t arrive on U.S. shores until 1989, and represented an idea in motorcycling that was sort of ahead of its time, despite being based on components as old as 1979.

The formula was fairly straightforward: take a simple, lightweight, and proven motor, and mount it in a simple, lightweight, and well thought out chassis, and make sure the suspension works right for the intended purpose. This is nothing groundbreaking, the British had been doing it for decades before their motorcycling industry folded up, moved away, and was sold off to the highest bidders, which is sort of how the GB500 was both too late and too early to the party–but we’ll get to that part later.

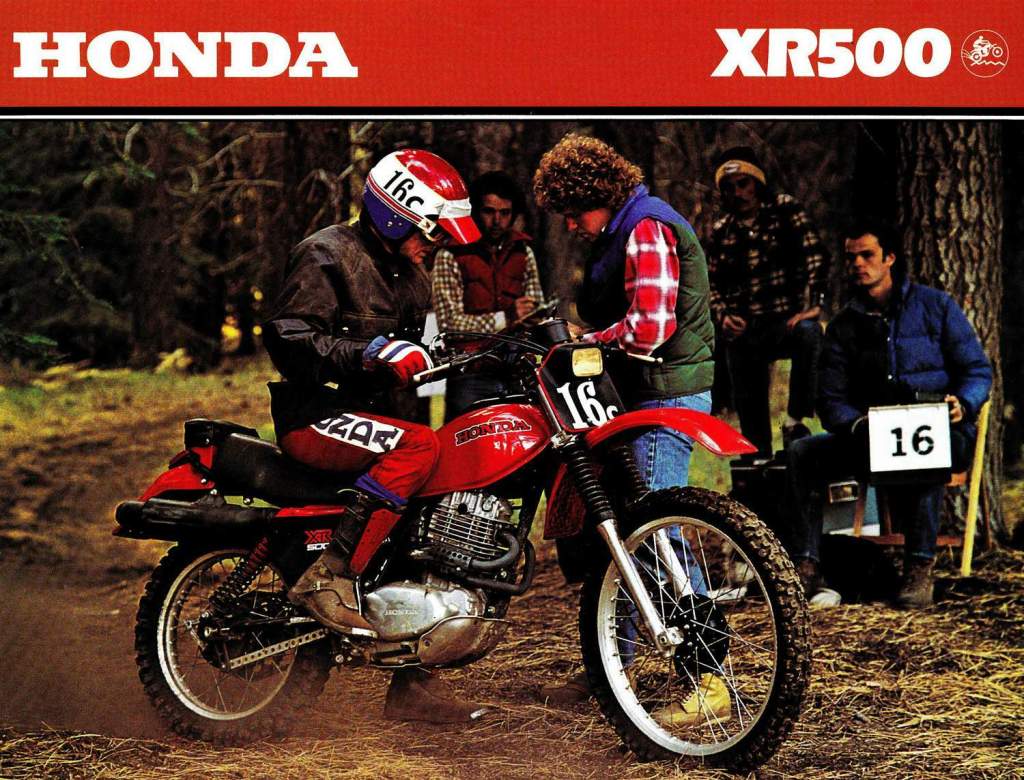

To get their simple and lightweight engine, Honda took from what they already had. The 498cc powerplant was plucked from between the frame rails of the much beloved XR500, a tough enduro/dual sport bike that debuted in 1979, making the motor a decade old by the time it made it into the GB500 in the U.S. While it was a bit of an aged design, the Honda Radial Four Valve Chamber motor (the one with the dual exhaust header despite the single cylinder), or RFVC for short, was still a very competitive engine for its cylinder configuration and displacement, and is still utilized today in the Honda XR650L. 35-ish horsepower from a single cylinder engine is still acceptable by modern standards, and was more than reasonable in 1989. Peak power was developed at “only” 7000 RPM, but the 500 was happy to make good, linear power all the way up and down the rev range–power was always where the rider needed it to be.

Suspension was nothing exotic either, with a standard telescopic fork in the front, with a standard short-style damper rod. While Honda helped usher the rear monoshock suspension into regular street use in the early-80s VF750 Sabre, Honda instead opted for a more traditional twin-coilover design typical of a Honda CB-whatever motorcycle of nearly any vintage or displacement. While simple, these components worked incredibly well together for the intended purpose of the motorcycle. The springs and shocks were standard motorcycle shop fare in 1989, and while not adjustable, could be exchanged quite easily and inexpensively to suit the rider’s weight and preferences. The “intended purpose,” as I’ve mentioned a couple of times now, did not require a high-tech, tight-tolerance race suspension, but rather a compliant ride, just stiff enough to inspire confident handling on rougher pavement. The GB500 was a factory-built café racer–make no mistake about it–tuned for the likes of the Isle of Man rather than Moto GP. This is another part of why the otherwise magnificent GB500 was only a two-model-year offering in the United States.

It wouldn’t be correct to say that the GB500 was a failure–it really was a fantastic motorcycle and continues to command a premium in the market to this day. But the single-cylinder café faced quite the conundrum: it was both ahead of and behind its time. It was about 25 years too late for the OG, clubman-bars-on-a-BSA-Gold-Star café racer crowd still working with leftover British Triumphs and Nortons that predate the collapse of the U.K. motorcycle industry. But it was also about 25 years too early for the resurgence of the retro-styled, brown-leather-seat crowd–like “Modern Classic” Triumph Bonnevilles, the 2011-ish CB1100, or the more recent Kawasaki W800. But in 1989, buyers didn’t want a more modern retro replica. Young buyers wanted new and flashy motorcycles on the cutting edge of technology, the type of stuff they were promised in contemporary films and television. The Kawasaki Ninjas and GPZs of the time, along with Honda’s own Interceptor and new Hawk GT were the hot bikes of the day. And their parents still largely preferred the 30-year-old BSA, Norton, and Triumph bikes over a new Japanese import. This made the GB500 a complete non-starter in the American market.

While exact GB500 importation numbers are unknown, approximately 2,000 units floated over from Japan. But sales were so slow in the U.S. that around 1,000 units were re-exported to the European market where buyers were more receptive to the unique experience the GB500 had to offer. These days, buyers appreciate the things overlooked in 1989, with good examples commanding three times their original $4,200 MSRP. A small price to pay for an extraordinary motorcycle with an interesting place in Honda’s history.