Chrysler in the late 1950s was giving the future a “Forward Look”–in more ways than one.

After the failure of Rambler to bring an electronic fuel injection system to market in 1957 in our last entry of Early EFI Chronicles, you may have expected Bendix to throw in the towel in the automotive EFI arena of the late 1950s. The situation with Rambler seemed too good to be true–the car would have been the fastest production car in 1957, was priced affordably, and was backed by a real effort to promote performance in the Rambler brand. And yet, it still failed to launch.

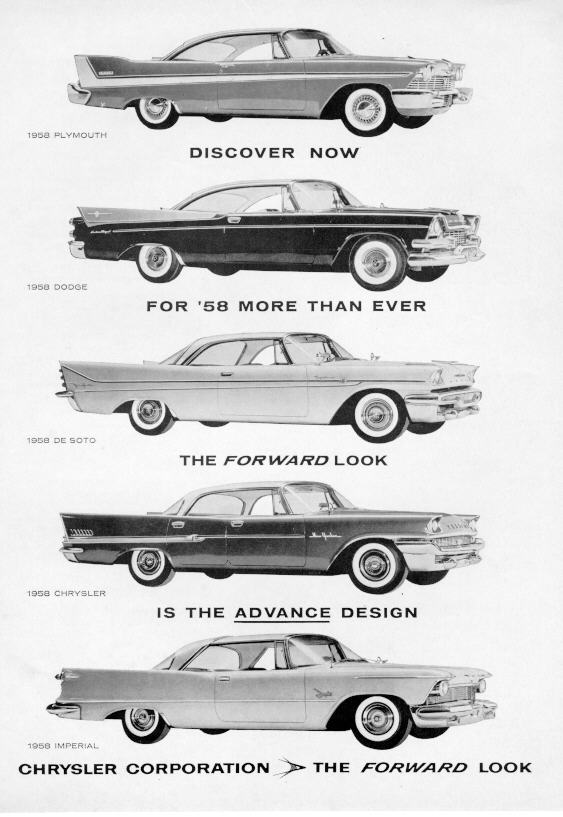

But in 1957, Chrysler Corporation had expanded its “Forward Look” design language to include its entire range, from the entry-level Plymouth Fury, all the way up to the fabulous Imperial, with Dodge, DeSoto, and Chrysler in between. Chrysler Corp. at this point never really had the manufacturing resources and capital of Ford or General Motors and, as a result, found it more difficult to compete in terms of price and brand recognition. In order to drive sales, Chrysler began to expand the idea of “Forward Look” from the design room and into the engineering room, coming up with a number of interesting innovations that, while not always immediately superior to those of their competitors, still managed to capture the imaginations–and checkbooks–of optimistic post-war Americans. Some innovations were small–push-button transmissions, retractable antennas, and even a dash mounted anti-skip record player–improvements that, while relatively inconsequential to performance and comfort, really gave car buyers a sense that Chrysler Corp. was ahead of its competitors, especially in the entry level and intermediate ranges. I think this feeling is best described by a 1957 Plymouth advertisement tagline: “Suddenly, it’s 1960!” In addition to this, Chrysler made some very real steps forward in more meaningful areas, such as introducing a line of hemispherically headed V-8 engines, known originally under the FirePower, FireDome, Red Ram, and Power Dome marquees, but known by every hot rodder and drag racer since as the early “Hemi”. Similarly, Chrysler’s new torsion bar front suspension significantly improved the handling of full-size sedans over its coil-sprung counterparts, reducing brake dive and body roll. An entire generation of stock car drivers and dirt track racers took notice, campaigning Dodges and Plymouths to innumerable successes for decades. At the very least, Chrysler Corp. was different in an age where Ford and General Motors were building cars that generally mirrored one another (as good as they may have been).

But what we’ll be focusing on again here is, once again, an option for the Bendix Electrojector Electronic Fuel Injection system that was (sort of) optional on 1958 Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, Chrysler, and Imperial automobiles. I explain this system into some detail in my first entry of Early EFI Chronicles about the Rambler from a year earlier with the same system. Nonetheless, a quick refresher is appropriate. Fuel injection holds a number of improvements over carburetion, including decreased fuel consumption through more uniform fuel metering, greater performance due to the increased fuel velocity in the intake, as well as encompassing a broader range of optimal operation conditions than a carburetor, among others. Bendix Electrojector electronic fuel injection further improved upon contemporary mechanical injection systems (Rochester Ramjet, Hilborn, etc.) by being less mechanically complex, less reliant on strong vacuum from the engine (although vacuum lines were still required), and possessing easier-starting characteristics–things that are less of an consideration for race cars and fighter planes, but very important improvements for a primarily street-driven vehicle.

Chrysler Corporation planned to capitalize on these advantages as well as continue their “Forward Look” philosophy into the engine bay atop their “Wedge” V8 engines (but not the Hemi) by offering the very same “computer” (in all reality just a transistor modulator unit)- controlled Bendix system that Rambler had attempted just a year earlier. While simplistic by today’s standards, this system was space-age technology to the average consumer, and contributed to furthering Chrysler’s image as, at least on the surface, an innovator. And where Rambler failed in 1957, Chrysler would be victorious for 1958. Well, not quite victorious, as only 35 cars would be produced with Electrojector and it would long be lost in the ether of automotive mysticism for a number of decades. But on the other hand, 35 Bendix Electrojector systems actually made it onto 35 Wedge motors, into 35 1958 model year Plymouth, Dodge, DeSoto, and Chrysler vehicles, before those 35 cars were sent to a dealership lot, and sold to 35 new car buyers who wanted their own taste of the future. (In reality, all 35 were likely special orders, but that doesn’t sound quite as victorious.) At the very least, that’s 35 more than Rambler can claim.

So, why only 35? And why haven’t we been driving electronically fuel injected vehicles for the last 62 years (in 2020)? Well, for starters, the EFI option cost $637.20 in 1958, which is creeping up on double the price of the option as Rambler would have offered it in 1957. This took Electrojector from a relatively affordable option to one that was overwhelmingly overlooked. Couple this with the 1958 economic recession in the United States and suddenly an expensive option on a full-size mid-range sedan only available with a premium-only gas-guzzling 361ci V-8 doesn’t sound like such a wise proposition, even if it does make 345 horsepower (SAE net). Actually, 1958 would mark the beginning of the end for the DeSoto marque as a whole, being wiped from the Chrysler brochure by 1961. Speaking of brochures, electronic fuel injection was advertised in exactly zero Chrysler Corp. promotional brochures from the 1958 model year, which also didn’t help matters. A situation which, ironically, is reverse image of Rambler advertising EFI in their 1957 brochures despite not actually producing a unit for consumers.

Besides cost issues, it also turns out that Bendix’s Electrojector system wasn’t quite as great as Rambler would have you believe, or even as good as I may have led you believe in the last issue of Early EFI Chronicles. While the system was mechanically simple, the modulator control box would prove to be quite troublesome, particularly due to crude early capacitors and moisture buildup in the transistors. Bendix also made a number of changes to Electrojector from its aircraft roots to allow for part-throttle flexibility characteristic of street driving. This made the system work pretty well on the street, but made it impossibly electrically complex for most auto mechanics to service or troubleshoot in 1958. In fact, nearly all, if not all vehicles equipped with Bendix Electrojector were converted to a carbureted intake or scrapped in the decade following their sale. Rumor is more than half were even recalled by Chrysler to have a 4-barrel carburetor installed shortly after sale. Only one original Electrojector-equipped Mopar exists today, a 1958 DeSoto Adventurer Convertible, a rare car in its own right. And even that car lived with a carburetor for decades and only by a stroke of luck was the restorer able to find and reunite the car with its original Electrojector system.

What we’re left with today is an interesting automotive vignette from another time, a couple of rare chrome badges, and a single car still traveling America’s highways as a glittering symbol of optimism from Chrysler’s “Forward Look” era.

In a 1956 Bendix company newsletter, president Malcolm Ferguson declared that electronic fuel injection “will replace the carburetor and improve performance.” Turns out that his vision would be a few decades early, but damned if he didn’t try in his own time.